Six years after his beer-piphany, the pieces are finally in place. On Sunday, March 15, Murphy’s grand plan will come to a fruition in the form of the Runner in Red 5K Run/Walk in Eisenhower Park in East Meadow.

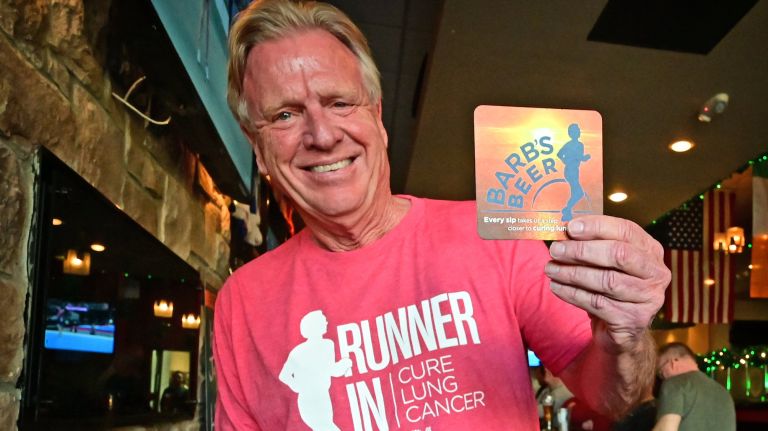

Murphy relates the story sitting over a beer at Prost Grille & Garten — the Garden City pub that will host the postrace party, in which all participants in the 5k can get a free pint of Barb’s Beer — a golden ale that was originally created in the state of Washington and that is now being brewed in small batches by several breweries in New York and Massachusetts.

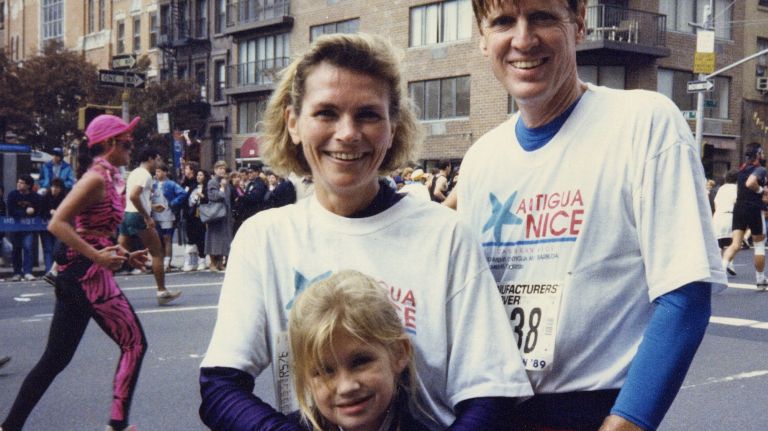

Barb and Tom Murphy with their daughter, Caitlin, during the NYC Marathon on Sunday, Nov. 5, 1989. Credit: Tom Murphy

Barb’s Beer is also a foundation — which raises money to support the work of Barb’s oncologist, Dr. Howard West, a Los Angeles-based leader in lung cancer education and research.

As for the “Runner in Red,” (Encircle Publications) that would be the name of Murphy’s first novel, published in 2018, which tells a story, based on a Boston Marathon legend, of a mysterious, crimson-clad woman who ran the race in 1951 — years before females were permitted to officially compete in the iconic 26.2-mile event.

All of it ties together aspects of the life that Murphy and his wife shared during their 33 years of marriage. “She loved running. She loved beer. She loved good conversation,” says Murphy. “And I think she would be very excited to see that action is being taken.”

‘Beautiful testimony’

Murphy’s commitment to the Barb’s Beer campaign is also an extraordinary and inspiring response to the loss of a loved one.

“Tom took a tragedy and turned it into a positive,” said Marty Brown, the longtime track and cross-country coach at Kellenberg Memorial High School who has known the Murphys since his days as a college runner at Western Washington University in Bellingham.

“He used his talents and his forward-thinking approach to life to make something good happen,” says Brown, who like Tom Murphy, grew up in Garden City.

“It’s a beautiful testimony to the strength of their relationship, and their shared passions,” says palliative care physician Dr. David Wu, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. “It’s also a reminder that everyone grieves in a different way.”

Some, Wu points out, follow the five stages of grief famously postulated by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. But, he says, more recent research suggests that not everyone deals with loss the same way.

Characteristic of his upbeat approach to life, Murphy would rather talk about Barb’s life than about his feelings regarding Barb’s death. He holds up a coaster and T-shirt featuring a profile of Barb taken from her finish line photo at the 2000 Boston Marathon, which she ran when she was 50 — the first time she’d done the race and seven years before she was diagnosed with the cancer that took her life in late 2013. “She got to be a very good runner,” he says proudly.

The daughter of a Boston city firefighter, Barb Mullen grew up in the suburb of Milton (one of her many charms, Brown says, was her endearing Boston accent. “‘She used to ask me, ‘Mahty, are you dating any nice girls?'”)

Barb met Tom, then a young teacher in the Boston school system, at a dance in the early 1970s. Murphy, who had been an outstanding high school runner at Brooklyn Prep, introduced her to running, buying her a pair of one of the first running shoes created for women (the Nike SL72), and taking her for jogs along the Charles River. When Tom was offered an opportunity to pursue an MFA in creative writing at the University of British Columbia, Barb — an interior designer by profession — eagerly embraced the adventure of a new life on the other side of North America.

It was the beginning of many moves, as Tom’s career changed from teaching and writing, and he became the sought-after creator of customer service programs widely used by the airline industry.

But whenever he was home, he and Barb enjoyed a ritual. “Every morning at 5:30, we’d go for a five-mile run,” recalls.

The couple, who eventually settled in Bellingham, a city near the Canadian border with Washington state, returned to the East Coast regularly and brought their running shoes with them. Tom and Barb ran the New York City Marathon seven times together.

Murphy now splits his time between Garden City and Plymouth, Massachusetts. The daily runs continue. Raised Catholic, Murphy says that while both he and his wife had lapsed from their religion as adults, “we never wavered in our belief that the soul is eternal.” During his now-solo runs, he says, “I really feel that Barb is right next to me.”

If so, she will be in the midst of the action at Eisenhower Park on Sunday, with Tom, the race director. He will be joined by their daughter, Caitlin Murphy, 38, who lives in Manhattan and has been active in the multifaceted campaign to honor her mom and raise funds for research.

As of March 9, there were 363 participants preregistered in the 5k, a strong showing for a first-time 5k. Moreover, NYU Winthrop Hospital has entered the event as a title sponsor; and, importantly, a big batch of Barb’s Brew is scheduled to be shipped to Garden City in time for Sunday’s postrace party.

That’s what Tom Murphy wants to focus on. Not the sadness of Barb’s death, not the loss he still feels. Barb wouldn’t have wanted it any other way.

“She never complained during her illness, never felt sorry for herself, never once a ‘why me?'” He pauses and smiles. “That’s why she deserves a beer.”

Living with grief

When Roslyn native Dr. Lisa Shulman lost her husband in 2012, the effect was devastating, beyond what she had expected.

“I mistakenly believed that because I’m a practicing neurologist, and care for people with serious neurological conditions, I’d do better when confronted with this experience of loss,” says Shulman, who now lives in Baltimore. “That was simply not the case. I had the rug pulled out from beneath me like anyone else.”

Six years later, Shulman — a professor of neurology at the University of Maryland — published a book on her experiences managing grief over the loss of her husband, William Weiner, who was also a doctor. “Before and After Loss: A Neurologist’s Perspective on Loss, Grief and Our Brain” (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018) is partially a memoir, but also examines the effects of loss on the brain.

“When we lose people that are really close to us, we don’t necessarily appreciate what a trauma and assault and threat it is to our identity,” she says. “Our whole lives are invested with these people, as they should be.”

Shulman compares the internal response to a fire alarm going off in the brain. “The brain is continually sending out signals of threat,” she explains. “‘You’re in trouble, you’re at risk.’ This constant alarm causes incredible chronic stress on the brain and the body.”

The ongoing state of high alert and stress can lead to a loss of identity and disorientation. “You begin to ask yourself ‘who am I in this world without that person?'”

Answering that question, managing the grief process and moving on is possible, however. One tool that Shulman used in her own recovery, and that she recommends in her book, is journaling: keeping a written record of one’s emotions and feelings and experiences during the grieving process. Meditation, cognitive-behavioral therapy, spirituality and religion are also helpful in managing loss. Not to mention personal pursuits.

“For some people, it could be drawing or photography; for others it could be time spent out in nature,” she says.

Shulman thinks that what Tom Murphy is doing to memorialize his late wife through Barb’s Beer and the Runner in Red 5K is a laudable example of working toward that goal. “People who do best over time are those who find comforting approaches to honor the people we love,” she says. “I can see the beautiful attachment and love between Barb and Tom in their story. He’s so inspired, he’s so energized to do these things. It’s a reflection of the incredible bond they must have had together.”